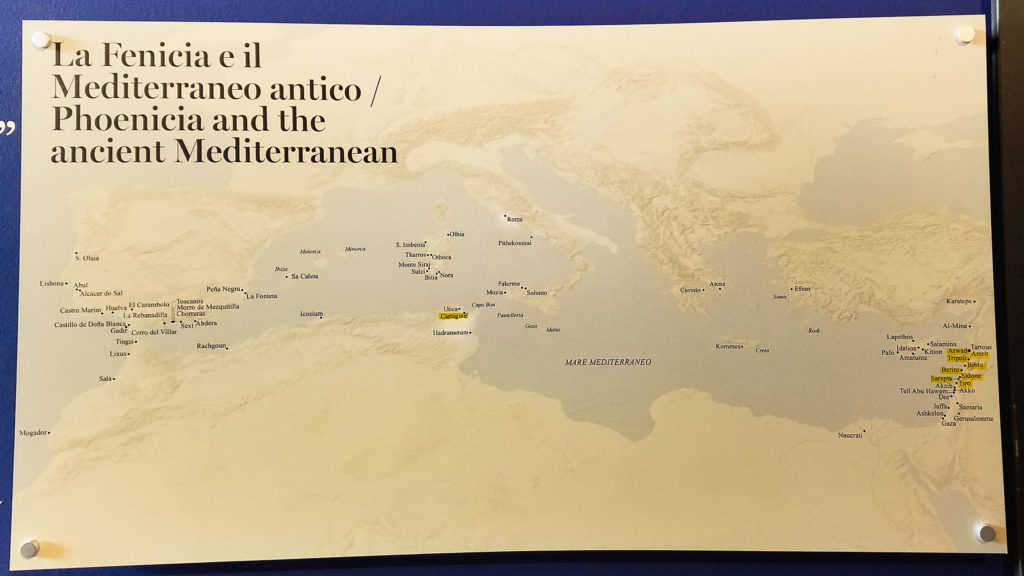

I love visiting the ancient sites of Rome. There is something special about seeing such famous places up close, and I am very lucky to learn so much about them through my classes at Temple Rome.

One of my favorite class trips this semester was a visit to a classic sight in the city: the Colosseum! I’ve been to the Colosseum before, but I had never been inside the site before for the trip. The Colosseum houses plenty of ancient Roman artifacts in its internal displays, but for our visit, we got to see a special exhibit on a different people: the Carthaginians!

In the ancient world, the Carthaginians were from their home city of Carthage in north Africa, where Tunisia is today. Carthage was originally settled by the ancient Phoenicians, who were from the Fertile Cresent area in the middle east. The city developed into the center of a major power starting from the 7th century B.C.E.

From late September this fall to the end of March next year, the Colosseum is housing a temporary exhibit on ancient Carthage. What perfect timing for our Race in the Ancient Mediterranean class! We learned about the Carthaginians in October and went to see the exhibit in early November.

Before this visit, I thought I had already gotten a close look at the Colosseum from the outside. Once I had stepped inside, I was amazed by how big the place really is!

We learned from Professor Bessi that this place was not always called the Colosseum. It was known as the Flavian Amphitheater in antiquity. The part of the word “amphitheater” comes from the ancient Greek word amphi, which means “on both sides.” This is different from an ordinary theater in the ancient world, which was had all the seats arranged in hemisphere around the stage. The Colosseum is an amphitheater because of it had seats all around (i.e., on both sides of) the center, where the spectacles took place.

The “Flavian” part of the place comes from the imperial dynasty that constructed the amphitheater. The Colosseum was constructed after 70 C.E. and took ten years to build under the emperor Vespasian, founder of the Flavian dynasty. It was not the first amphitheater in the Roman world: the earliest one is in Pompeii, which had an amphitheater from 80 B.C.E.! The place was the center for all sorts of visual entertainment, including parades, animal fights, and the famed gladiator games. The Romans added underground structures to the center later on and could flood the space for recreations of naval battles.

The spectators of these events sat in different places depending on their social class. The high-ranking senators got the best spots in the front with reserved seats (complete with specific names carved into them) while average Romans had to find their own seats. The Colosseum could hold 600,000 to 800,000 people for a single event! The games stopped after the emperor Constantine converted to Christianity in the 4th century C.E., and after that, the massive amphitheater was used for defense in the Middle Ages and for its building material to construct the nearby Piazza Venezia during the Renaissance.

What a view of the theater!

What a view of the theater!

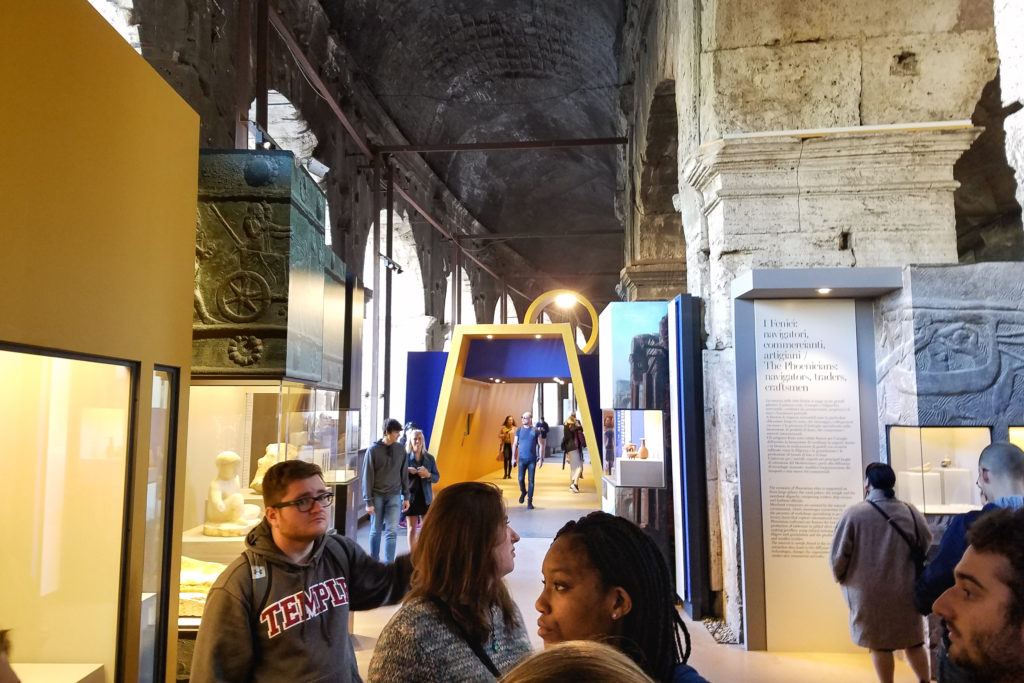

We began our tour of the exhibit with a discussion on the Phoenicians, whose name derives from an ancient term meaning “red people,” based on the myth of the sun getting too close of the people of the region and giving them quite the tan (and, I can imagine, quite a red sunburn). They were an active seafaring people who settled across the ancient Mediterranean. Sicily and north Africa were major sites in their travels.

Looking around the exhibit.

Looking around the exhibit.

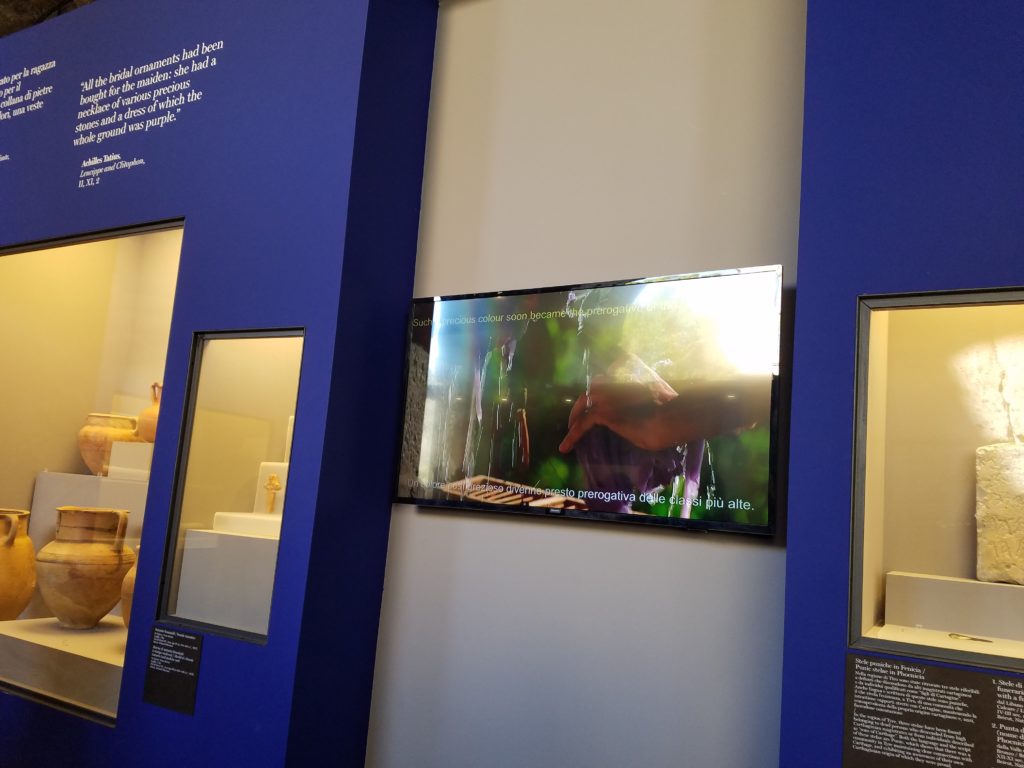

The Phoenicians were highly sophisiticated craftspeople. They were especially famous for glass and were one of the first civilizations to mass produce goods for trade. Purple dye was another famous Phoenician export. The color, called Tyrian purple after the settlement of Tyre, was made from crushing snail shells and was very expensive to produce. Because of this, only the wealthiest people in the ancient would could to wear purple clothing, and the color purple became associated with power and royalty.

We saw collections of artifacts excavated from sites associtated with ancient Carthage on display through the entire exhibit. What fascinated me the most is the number of museums involved in creating this exhibition. There were so much intricate art, pottery, and jewelry on display! And all of these were on loan from different museums across Europe and Africa!

The exhibit also included a lot of digital content as well. We saw the structure of Carthage change through time on a screen in the hallway. We also saw a video about both land-based and underwater excavations at major sites. It’s interesting to see how people have interacted with Carthage in the past and the present.

Part of the special exhibition featured interpretations of Carthage in more recent media. One of the famous impacts of the ancient Carthaginians was the story of Dido, the queen of Carthage in the ancient Roman epic, the Aeneid. I read parts the Aeneid for AP Latin class, and one of the sections was about Dido. There was a painting inspired by her story on display in the hallway.

Unfortunately, the Carthaginian queen’s story does not have a happy ending. She is distraught after Aeneas, the main character of the epic, leaves Carthage to found Rome. Dido curses Aeneas and his descendants, saying that in the future, the Romans and Carthaginians will never be friends. Publius Vergilius Maro, the author of the Aeneid, shifted the blame to this episode to explain the real-life tensions between Rome and Carthage.

Taking the blame for tensions is not the only blow to the Carthaginians’ reputation among their neighbors in the ancient Mediterranean. The Romans also supported the Greek claim that the Carthaginians sacrificed their own children. This was a negative stereotype attached to the Carthaginians through their existence. From evidence found at tophets, open-air spaces dedicated to holding grave monuments for children, it is probable that the Carthaginians practiced substitution sacrifices, in which they sacrificed animals instead of children to their gods.

The Carthaginians were polytheistic civilization with deities analogous to those of the ancient Greeks and Romans. A major god in their religion was Baal Hammon, who was like Zeus or Jupiter in Classical mythology. Many inscriptions on the monuments in Carthaginian tophets are dedicated to Baal.

Another interesting figure in Carthaginian culture was the god Asclepius, who was the god of healing. There is a stone with a trilingual inscription to the deity. There are dedications to the god in ancient Greek, Latin, and Punic (the language of the Carthaginians). The god is referred to as “Asklepius” in ancient Greek, as “Aescepius” in Latin, and “Eshmun” in Punic on the tablet.

The Carthaginians believed in an afterlife, as seen from their funerary art. Professor Bessi pointed out a special image in the exhibit. The rooster in the art represents the human soul travelling to the fortified city of the deceased, where the spirits of the ancestors are waiting. The picture was displayed above a collection of grave goods. Like the Greeks and Romans, the Carthaginians buried their deceased with pottery and other objects.

We looked at the depiction of the Phoenician afterlife through the picture of the rooster (symbol of the soul), the fortified city (land of the deceased), and the spirits of the ancestors (on the left).

We looked at the depiction of the Phoenician afterlife through the picture of the rooster (symbol of the soul), the fortified city (land of the deceased), and the spirits of the ancestors (on the left).

It was interesting to see the cultural aspect of the ancient Carthaginians up close. In my Roman history classes in high school and at Holy Cross, I had only learned about the Carthaginians through readings about the Punic Wars, where were a series of three conflicts between Rome and Carthage that lasted for over 100 years. What I didn’t learn was the fact that there were trade agreements between the two civilizations before the conflict over Sicily that started the wars.

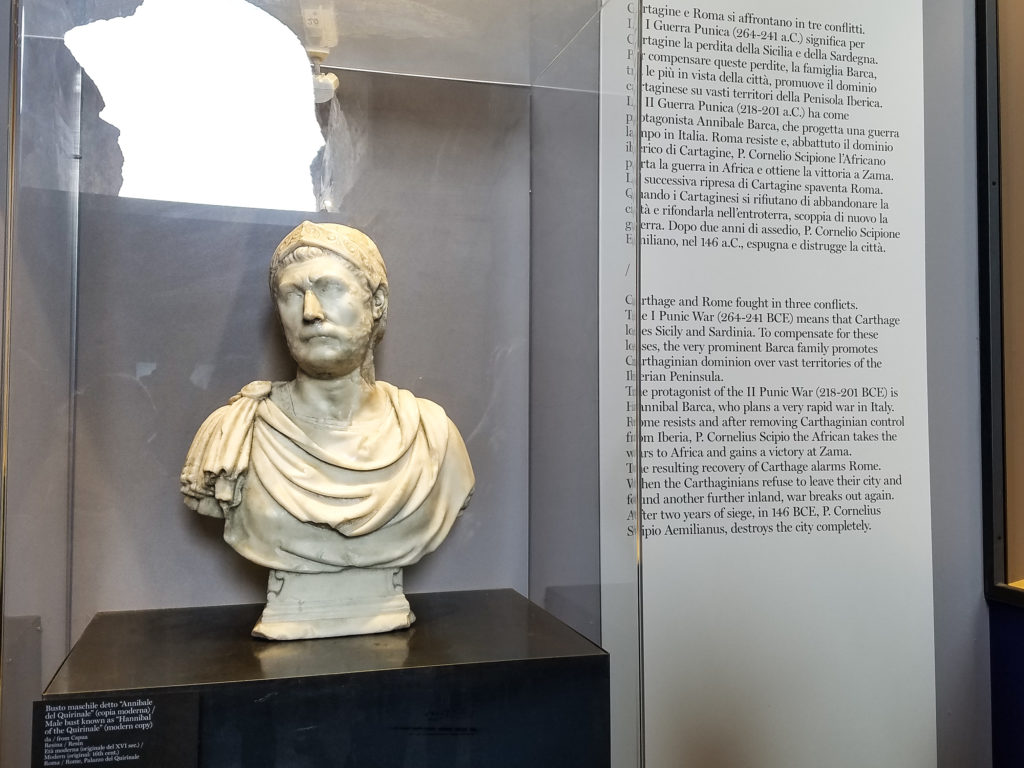

A key Carthaginian whose name has been remembered in history is Hannibal Barca, who was a formidable general during the Second Punic War. He is famous for his cunning military strategies and for leading an army of elephants against the alps. We saw a bust of Hannibal in the Colosseum. Fitting, considering what a spectacle that event must have been!

Carthage fell at the end of the Third Punic War in 146 B.C.E. The major Roman rhetoric against Carthage at the time was from the end of Cato the Elder’s speeches, which is often abbreviated to the famous “Carthago delenda est.” (Latin for “Carthage must be destroyed.”) The city was razed to the ground and salt sprinkled on the land to prevent rebuilding. Carthage became a province of Rome later on.

However, the Carthaginians lived on in various forms of media. We saw clips from movies and excerpts of songs based on the Carthaginians on our way out of the exhibit.

I caught a beautiful glimpse of the Roman Forum from the balcony just outside the bookstore. (You bet I bought some souvenirs from the exhibit! Limited time merchandise.) What a beautiful day to take in the sights of Rome!

I took one last glimpse at the “Carthago” sign outside of the entrance before leaving to catch the Metro back to campus. I am grateful for Professor Bessi for giving us this special opportunity to see a temporary exhibit. Cato the Elder may have constantly declared that Carthage must be destroyed, but here it has been remembered and its culture and people better understood thanks to the exhibit.