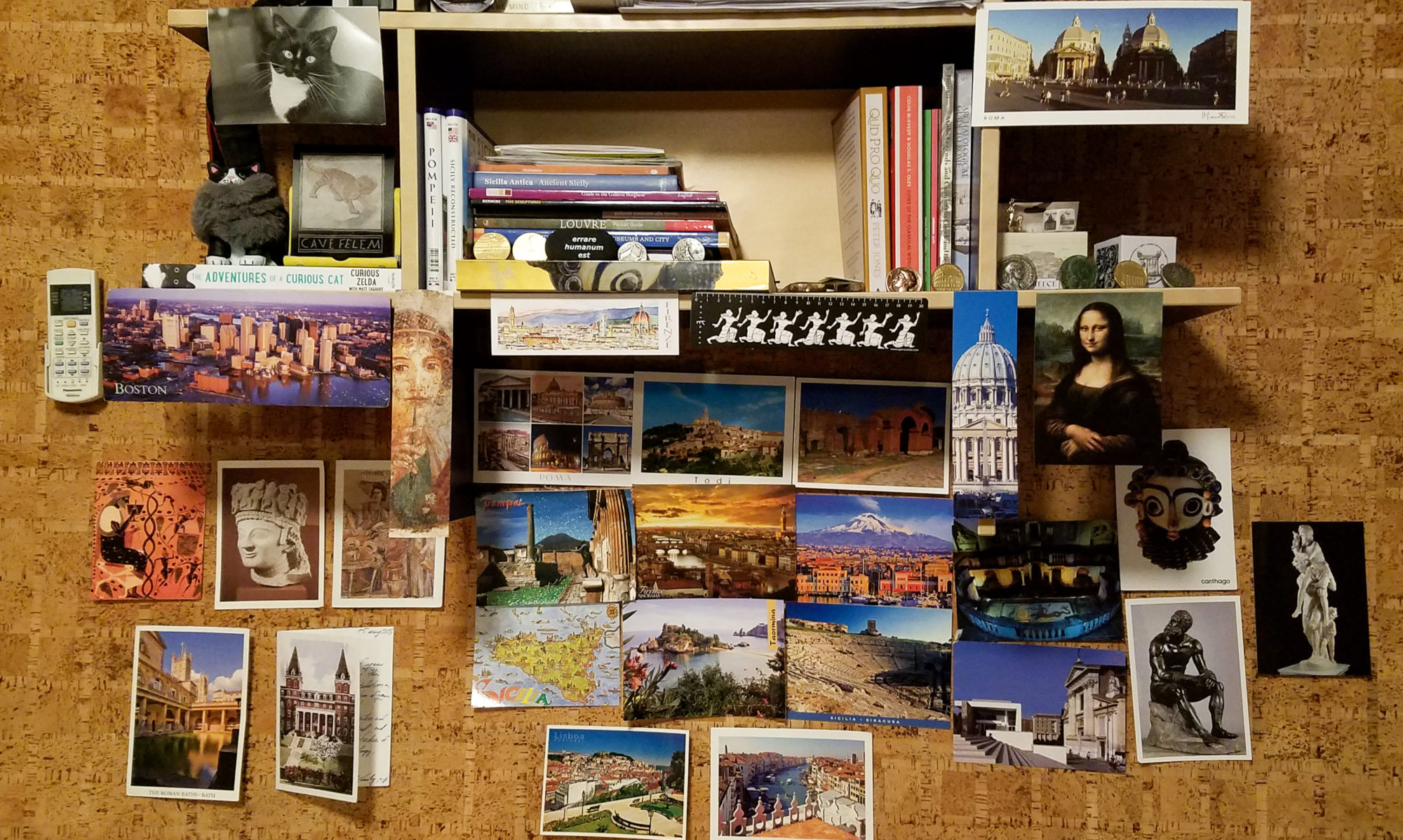

As I settle into the second half of the semester (how time flies!), I would say that my favorite part of studying abroad is getting to learn through direct experience. I love learning new things both in and outside of the classroom.

For my Race in the Ancient Mediterranean course this semester, I am learning about the ancient world through not only examining the histories of understudied people in the ancient Roman Empire, but also through seeing artifacts with my own eyes in Rome.

On our second trip of the semester, we went to the Capitoline Museums (Musei Capitolini in Italian) on top of the Capitoline Hill. The museums are the oldest in Rome, built in the 15th century during the Renaissance, when ancient Greek and Rome were the main themes of European culture and art. The first exhibits were made of bronze statues that the Pope offered to the city of Rome, and from here came the museums as they stand today.

I was in awe even before I got to the museum. Instead of heading to the classroom that Thursday morning, I took the Metro to the Colosseo stop and admired the huge monuments all around me. In addition to seeing the Colosseum outside the Metro stop, I caught a few glimpses of the Roman forum on my walk to the Capitoline Hill.

I found Professor Bessi and my classmates on top of the hill (which was not too taxing for my legs; all the stairs at Holy Cross have prepared me well for my semester abroad). After getting into the museum for free thanks to the Musei in Comune (MIC) cards we got at the beginning of the semester, we walked into the courtyard.

We looked at a collection of stone slabs with images of women carved into them. Professor Bessi said that these were originally from a temple in the Campus Martis that was erected in the memory of the emperor Hadrian, who ruled the Roman Empire in the 2nd century C.E. The carvings came from the base of the temple and represent the different provinciae (plural of the Latin word provincia, from which he get our word “province”) around the empire.

Hadrian was known for being a Roman emperor who spent little time in Rome. He was fascinated by other cultures, especially Greek culture, and strove to integrate even the most remote provinces in the empire and instill a sense of common Roman identity among all the people. The temple honor him captures this aspect of his personality by featuring each of the provinces, represented by women (nouns have genders in Latin, and provincia is feminine) depicted in the Greek style.

We headed indoors and stopped at the massive Palazzo di Conservatori. I was awestruck by the gorgeous paintings that lined the entire room from wall to wall. There was not a single part of the room that was not decorated with art.

The room, whose name means “the Conservator’s Palace” in Italian, was built in the 16th century. All the artwork in the room was inspired by the ancient Romans and features scenes from Roman history as told by the ancient historian Livy, who wrote about the origins and history of Rome in his Ab Urbe Condita Libri (Books from the Founding of the City) in the 1st century B.C.E.

All around the room, I saw painting of the foundation stories of Rome. I felt like I was going back in time, back to the first time I saw Latin in middle school. One of the first stories I read in class was the myth of the twins Romulus and Remus and how they were raised by a she-wolf. Romulus, after whom Rome is named, is said to have founded the city in 753 B.C.E.

I learned more about the earliest days of Rome as I continued into more advanced levels of Latin in high school. Now, as a college student, I got to see all of what I learned in front of me!

The art depicting the story of Rome continued into the next room, where we stopped to look at one of the bronze pieces gifted by the pope in the earliest days of the museum. The bust of Lucius Junius Brutus, the leader of an aristocratic revolt that drove out the last king of Rome, represents a major shift in Roman history: the shift from monarchy to republic in 509 B.C.E. The bronze portrait of him, however, is certainly not from the 6th century B.C.E. It was much more likely made centuries after in a retelling of the tale.

Another wave of nostalgia hit me as we walked into the next room and stopped at a piece that my teenage self would have recognized from her books. I got to see the famous Lupa Capitolina (Capitoline Wolf) with my own eyes! The detail on the piece is remarkable: such a sharp contrast between the roughness of the she-wolf’s fur and Romulus’ and Remus’ skin!

These were things I didn’t notice when I first saw a picture of the Capitoline Wolf in my seventh-grade Latin textbook. Eight years later, I am going on a field trip to the Capitoline Museums, where I can see the sculpture in person!

It is amazing to see that story of Romulus and Remus and the she-wolf has lingered for so long after 753 B.C.E. What amazed me more was the story about this piece that Professor Bessi told us at the museum. It turns out that the Lupa Captiolina did not always look the way it does today. In fact, it was really only the wolf! The twins were not added until the 16th century C.E.!

It was thought that the wolf was an ancient piece while the smaller sculptures of Romulus and Remus were Renaissance additions. There was a conference years ago at which chemical analyses on the base of the piece revealed that the she-wolf was sculpted in the middle ages!

In the next room, we saw a piece that was actually ancient: a Greek krater (a vessel for mixing wine) dating back to the 7th century B.C.E. The Aristonothos krater, as it is called because of the potter’s signature visible in the ancient Greek inscription, depicts a scene from Homer’s Odyssey, an ancient Greek epic about Odysseus’ journey home after the Trojan War. I had read about Odysseus outwitting a giant one-eyed cyclops when I read the Odyssey in class, but seeing the scene on a vase in front of me was a different experience in itself!

The vase was uncovered at a site where the ancient Etruscans used to live. The Etruscans were a dominant force in central and northern Italy before 753 B.C.E., and they engaged in a lot of trade with the ancient Greeks. Greek pottery was in high demand for the ancient Etruscans, and through the acquirement of physical goods came the spread of Greek language, culture, and religion.

The inscription and imagery on the Aristonothos krater captures this perfectly. And it shows that ancient people had a wicked sense of humor – the cyclops met his downfall because he drank his wine unmixed, and now he is on a vessel designed for mixing wine!

We headed toward the recently-renovated part of the museum, where the original bronze statue of the emperor Marcus Aurelius is on display. There is a replica of this piece at the top of the Capitoline Hill, just outside the museum.

Professor Bessi mentioned that when the statue was uncovered in the Middle Ages, people thought it was a sculpture of the emperor Constantine, who ruled the Roman Empire over a century after Marcus Aurelius did. The funniest part about this room is the fact there is actually a statue of the real Constantine across from the bronze statue of Marcus Aurelius and the marble sculpture of the lion and the horse!

The newly-renovated part of the museum also houses some ancient ruins found in the area. There are pieces of an ancient temple dedicated to the Capitoline Triad – the gods and goddesses Jupiter (or Jove), Juno, and Minerva. It was interesting to catch a glimpse of the excavation process in the middle of a modern renovation of the Capitoline Museums. There is even a wall of the Capitolium Jovis (a temple for Jupiter; there was one of these at every Roman colony) standing inside with a smaller-scale replica beside it!

After our walk through the remnants of the temple, we visited the Horti Maecenatiani, or the Maecenean Gardens. Maeceneas was a friend of the emperor Augustus in the first centuries B.C.E. and C.E. and was known for his wealth and love of art. He was also involved with the ministry of culture and displayed lots of Greek sculptures in his gardens on the Esquiline Hill. A lot of the statues are Roman copies of Greek originals, but some of the pieces are made of real Pentelic marble, which comes from an area north of Athens.

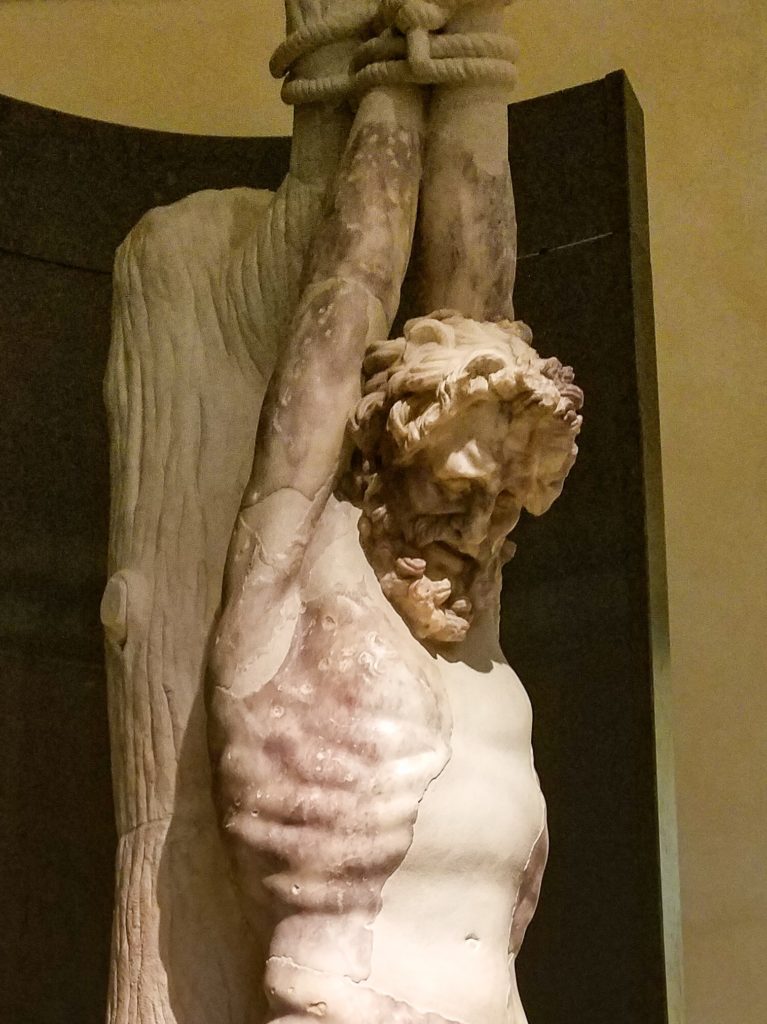

One of the most memorable statues for me was a sculpture of the mythological satyr Marsyas, who made the grave mistake of boasting that his music was greater than that of Apollo, the god of music. As his punishment, he was skinned alive. I found the contrast between the pale marble of his skin and the sheer redness of his raw flesh very striking. It really gets the message across: don’t be a braggart!

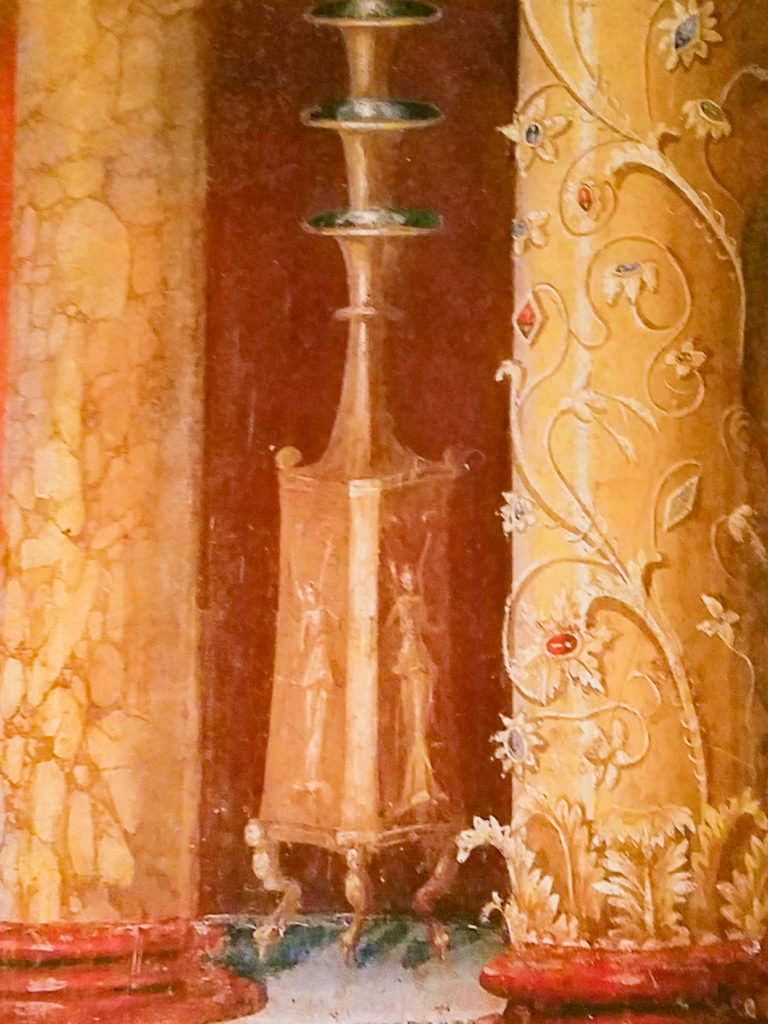

In addition to the wealth of statues in Maecenas’ gardens, there is also a large collection of jewelry in the museum. The golden pieces and their sparkling gemstones were in such good condition that I thought they were modern accessories in the fashion district of modern Rome! You can hardly tell that they’re from the first century C.E. And it wasn’t only people who wore these: the ancient Romans used jewelry to decorate pillars as well!

We walked through the basement of the museum and looked at some gravestones. The inscriptions were still legible on most of them, and I had a lot of fun practicing my ancient Greek and Latin! According to Professor Bessi, Greek was the universal written language of all the ethicities in ancient Rome. We spent a longer time looking at the gravestone of a Jewish woman who had the majority of her funerary inscriptions in Greek but the last part of it in Hebrew. Amazing to see cultures overlap!

We were in for quite a treat when we got to see the Roman Forum from a good vantage point in the museum! I loved seeing all of the space outside the museum from one spot! It was my first time seeing the Forum, and it was a wonderful experience to process the breathtaking view!

Our last stop was at another famous piece in the Capitoline Museums: the Dying Gaul. The ancient Gauls were a Celtic people who lived north of Italy in the alps and to the west where France is today. Julius Caesar waged war against several Gallic tribes and recorded his battles in his Commentarii de Bello Gallico (Commentaries Regarding the Gallic Wars) in the 1st century B.C.E. I read part of Caesar’s work in high school. I was excited to see the artwork in person!

For a decade, the Gauls were his enemies, yet he chose to respect them by featuring a piece depicting them gracefully in defeat. The Dying Gaul is a Roman copy of a Greek original thought to have been commissioned by the King of Pergamum, an area to the east, centuries before Caesar was born. The man in the sculpture is identifiable as a Gaul by his hairstyle and jewelry around his neck. He is about to collapse, but keeps most of his composure despite the pain of defeat.

It fascinates me how of all the ways Caesar could have represented his fallen enemies, he chose to display this piece in his private estate. No caricature of the Gauls or humiliating trophies in this statue! Talk about sportmanship!

I left the museum very pleased with what I saw. For years, I have been studying the historic and cultural contexts of the ancient world, but have very rarely seen them outside of paragraphs of text. Seeing all the artwork in three dimensions and with my own eyes – now, that’s what I call an enriching experience! I cannot imagine another place that can offer such a fulfilling expansion of my knowledge in this way as the Capitoline Museums.

Having read this I believed it was really informative.

I appreciate you finding the time and energy to put

this article together. I once again find myself personally spending a lot of time both reading and

posting comments. But so what, it was still worth

it!

Like!! I blog quite often and I genuinely thank you for your information. The article has truly peaked my interest.